The sins of the father shall be visited upon the son. This, I’m sure, is exactly what Enrico Scrovegni was worried about. Maybe that was good, as this was the impetus for him to build The Scrovegni Chapel and to commission Giotto to decorate it. (The Chapel is also referred to as the Arena Chapel, as it stood on land that was once the site of a Roman arena.)

Now, Italy is famous for its painted chapels. Michelangelo’s masterpiece, The Sistine Chapel, immediately springs to mind. Anyone visiting Rome for more than one day has this high on their list of things that must be seen. The passion, the drama, of the ceiling and “The Last Judgement” leave one in awe (as well as feeling a touch of under-accomplishment with their own life).

But let’s backtrack about 150 years before that chapel to another one that heavily influenced Michelangelo’s masterpiece.

Scrovegni’s family was wealthy, very wealthy. It was the source of their wealth that gave Enrico some worry about his place (and that of his father, Reginaldo) after he left the earth. The family were bankers – sounds pretty respectable, doesn’t it? In the 1300s, they were referred to as moneylenders (or usurers), you know, the ones that Jesus threw out of the temple. The thought was that Enrico had to atone for both Reginaldo and his sin of usury. Dante himself condemned Reginaldo as a usurer in Canto 17 of Hell. (How do you know it’s Reginaldo? In the inner ring of the Seventh Circle of Hell, the man is identified by the “azure pregnant sow inscribed as an emblem on the white pouch”; the azure pregnant sow was on the Scrovegni coat of arms.) Pretty high-profile condemnation, so a pretty big gesture was required!

Giotto was considered a very important painter at the time. He had studied under another master, Cimabue, but according to Dante “Once Cimabue thought to hold the field as painter; Giotto now is all the rage, dimming the lustre of the other’s fame”. Giotto was considered the first of the great artists of the Renaissance. He had already done work for the Franciscan friars in Assisi (yes, St. Francis of Assisi’s Basilica), as well as for the Pope on St. John Lateran in Rome. He was already in Padova working on St. Anthony of Padua’s Basilica and he also worked on Padova’s Palazzo della Ragione. This was a few years before he became the chief architect of the Florence Cathedral, the Duomo (where he is buried) and his famous bell tower “Giotto’s Campanile” that was started in 1334. A pretty impressive resume indeed!

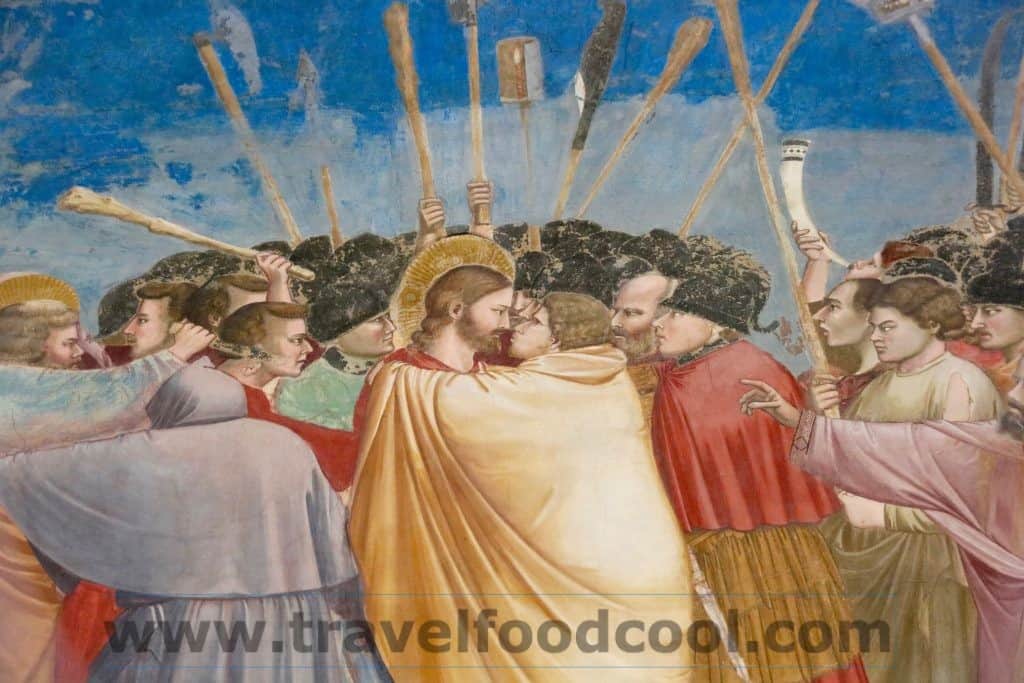

Enrico Scrovegni commissioned Giotto to tell the story of Mary, from her barren parents wanting a child (a fact I did not know) to her marriage to Joseph and to the birth of Jesus, and the story of Jesus from birth to the the Passion of Christ and The Universal (Last) Judgement. For extra measure, Giotto also painted the roof blue with stars.

The frescos which cover the entire walls were completed in two years (I still can’t believe that). Between 1303 to 1305, Giotto, who started the project at age 36, completed the frescos with the help of his 40 assistants in 625 work days. To paint a fresco, the wall is plastered and then painted while the plaster is still wet or fresh (“fresco”). One must work quickly before the plaster dries as it will not absorb the paint if dry. The statues that reside in the chapel were created by another great of the time, Pisano.

The purpose of the chapel was two-fold. It was the family’s private chapel as well as their funeral monument. The family had a private entrance from the Palace (this is now the public entrance to the Chapel) and there was a public entrance in the back.

In January 1305, two months before the Chapel’s completion, the neighbours, who happened to be The Church of the Hermit monks, complained about the Chapel. They claimed it was too grandiose, more of a church than a private place of worship, and that it was less a monument to God than it was to Scrovegni. Truth be told, they were worried that it would take worship “business” away from their church. This resulted in the apse and transept having to be demolished. This caused a slight problem, as the apse was where Scrovegni was planning his tomb. The area had to be redesigned, which is obvious as it lacks the same symmetry of the rest of the Chapel.

Giotto’s planned symmetry is apparent. The north side shows seven panels of Vices, while the south side has seven panels of Virtues. The thinking was that with the use of the virtues, humanity would overcome the vices or obstacles.

The panels also gave Giotto the chance to show off and to sculpt with his paint. Injustice, as one example (below), has raised trees which give the panel a more life-like quality.

The stories of the lives of Jesus and of Mary cover the main north (Jesus) and south (Mary) walls above the Vice and Virtue panels.

Giotto’s ability to show human emotion in both their expressions and gestures (example shown above in the Massacre of the Innocents) – the tears on the mother’s face and the soldier who is grabbing the baby, his body language, his head and shoulders hunched, he looks away in shame – are what set him apart from other painters of his time.

The Last Judgement is telling. It features Enrico Scrovegni wearing violet, the colour of penitence, as well as moneylenders in hell. The newly dead are seen crawling from the graves below his feet. To his right is the terrifying scene of hell. Sadly, the Last Judgement is the most damaged section of the Chapel, and the frescos have been partially destroyed by “salt bloom”.

Scrovegni’s enjoyment of his Chapel was short-lived. in 1320, he fled the civil wars of Padova for Venice. He died in Venice in 1336. He is buried with his second wife, Jacopina D’Este, in his Chapel.

The Chapel has also had its up and downs. In 1817, the portico collapsed which was followed by the Palace destruction in 1824. The City of Padova bought the Chapel in 1881. It was affected by bombing during World War II. It has recently re-opened after a 20-year restoration.

Admittance is now by timed ticket and limited to groups of 25 for a 15-minute visit. Like a visit to the Last Supper in Milan, you enter through temperature and air controlled glass doors. The system monitors the air and protects the frescos from further damage.

The Scrovegni Chapel is considered on of the greatest masterpieces of Western art and I highly encourage you to visit it when you’re next in the Veneto,

ELIN’s TIP: Book your tickets in advance, as entrance numbers are timed and limited. Click here.

Where: 8 Piazza Eremitani, Padova, Italy 35121; When: Open daily from 9am – 7 pm (tickets purchased for Tuesday to Sunday include also the admission to the Civic Museum of Eremitani and to Palazzo Zuckermann)